Elizabeth I, the

last of the Tudor monarchs, died in 1603 and the thrones of England and Ireland

passed to her cousin, James Stuart.

Unlike his mother, James is a Protestant. He is also undeniably the next in line of succession to Elizabeth's throne. Elizabeth is the last surviving descendant of Henry VIII, the only adult son of Henry VII. With her death the succession moves to the line of Henry VII's eldest daughter Margaret married in 1503 to James IV of Scotland.

Margaret's two senior grandchildren are the first cousins Mary Queen of Scots and Henry Darnley, the parents of James VI. His claim is clear. But Elizabeth refuses to acknowledge him as her successor, until finally indicating this intention on her deathbed.

No doubt Elizabeth reasons that an element of uncertainty will keep her Scottish cousin (almost exactly the same age as her last favourite ,Essex) on his best behaviour. She is proved right.

He is for his age the premier Prince who

has ever lived. He has three qualities of the soul in perfection. He apprehends

and understands everything. He judges reasonably. He carries much in his memory

and for a long time. In his questions he is lively and perceptive, and sound in

his answers. In any matter which is being debated, be it religion or any other

thing, he believes and always maintains what seems to him to be true and just.

He is for his age the premier Prince who

has ever lived. He has three qualities of the soul in perfection. He apprehends

and understands everything. He judges reasonably. He carries much in his memory

and for a long time. In his questions he is lively and perceptive, and sound in

his answers. In any matter which is being debated, be it religion or any other

thing, he believes and always maintains what seems to him to be true and just.

He is learned in many tongues, sciences and affairs of state, more so, I dare say, than any others of his realm. In brief, he has a marvellous mind, filled with virtuous grandeur and a good opinion of himself.

Unlike his mother, James is a Protestant. He is also undeniably the next in line of succession to Elizabeth's throne. Elizabeth is the last surviving descendant of Henry VIII, the only adult son of Henry VII. With her death the succession moves to the line of Henry VII's eldest daughter Margaret married in 1503 to James IV of Scotland.

Margaret's two senior grandchildren are the first cousins Mary Queen of Scots and Henry Darnley, the parents of James VI. His claim is clear. But Elizabeth refuses to acknowledge him as her successor, until finally indicating this intention on her deathbed.

No doubt Elizabeth reasons that an element of uncertainty will keep her Scottish cousin (almost exactly the same age as her last favourite ,Essex) on his best behaviour. She is proved right.

He is for his age the premier Prince who

has ever lived. He has three qualities of the soul in perfection. He apprehends

and understands everything. He judges reasonably. He carries much in his memory

and for a long time. In his questions he is lively and perceptive, and sound in

his answers. In any matter which is being debated, be it religion or any other

thing, he believes and always maintains what seems to him to be true and just.

He is for his age the premier Prince who

has ever lived. He has three qualities of the soul in perfection. He apprehends

and understands everything. He judges reasonably. He carries much in his memory

and for a long time. In his questions he is lively and perceptive, and sound in

his answers. In any matter which is being debated, be it religion or any other

thing, he believes and always maintains what seems to him to be true and just.He is learned in many tongues, sciences and affairs of state, more so, I dare say, than any others of his realm. In brief, he has a marvellous mind, filled with virtuous grandeur and a good opinion of himself.

Thus James VI of Scotland also became James I of England. The three

separate kingdoms were united under a single ruler for the first time, and

James I and VI, as he now became, entered upon his unique inheritance.

James had awaited

Elizabeth's death with eager anticipation, because of the wealth and prestige

the English crown would bring him. But, as this canny monarch must have known

all too well, the balancing act he would henceforth be required to perform was

not an easy one.

England, Scotland and Ireland were very different countries, with very different histories, and the memories of past conflict between those countries - and indeed, of past conflict between different ethnic groups within those countries - ran deep.

England, Scotland and Ireland were very different countries, with very different histories, and the memories of past conflict between those countries - and indeed, of past conflict between different ethnic groups within those countries - ran deep.

To make matters trickier still, each kingdom favoured a different form

of religion. Most Scots were Calvinists, most English favoured a more moderate

form of Protestantism and most Irish remained stoutly Catholic. Yet each

kingdom also contained strong religious minorities.

In England, the chief such group were the Catholics, who initially

believed that James would prove less severe to them than Elizabeth had been.

When these expectations were disappointed, Catholic conspirators hatched

a plot to blow both the new king and his parliament sky-high.

The discovery of the Gunpowder Plot served as a warning to James, if any

were needed, of the very grave dangers religious divisions could pose, both to

his own person and to the stability of his triple crown.

The Gunpowder Plot

The plot was revealed to the authorities in

an anonymous letter sent to William Parker, 4th Baron Monteagle, on 26 October 1605. During a search of

the House of Lords at about midnight on 4 November 1605, Fawkes was

discovered guarding 36 barrels of gunpowder—enough

to reduce the House of Lords to rubble—and arrested. Most of the conspirators

fled from London as they learnt of the plot's discovery,

trying to enlist support along the way. Several made a stand against the

pursuing Sheriff of Worcester and his men at Holbeche House; in the ensuing battle Catesby was one of those shot and killed. At

their trial on 27 January 1606, eight of the survivors, including Fawkes,

were convicted and sentenced to be hanged, drawn and quartered.

The plot was revealed to the authorities in

an anonymous letter sent to William Parker, 4th Baron Monteagle, on 26 October 1605. During a search of

the House of Lords at about midnight on 4 November 1605, Fawkes was

discovered guarding 36 barrels of gunpowder—enough

to reduce the House of Lords to rubble—and arrested. Most of the conspirators

fled from London as they learnt of the plot's discovery,

trying to enlist support along the way. Several made a stand against the

pursuing Sheriff of Worcester and his men at Holbeche House; in the ensuing battle Catesby was one of those shot and killed. At

their trial on 27 January 1606, eight of the survivors, including Fawkes,

were convicted and sentenced to be hanged, drawn and quartered.

Stuart rule in England: AD 1603-1642

In 1606 James I supports new English efforts (the first since Raleigh) to establish colonies along the coast of America, north of the Spanish-held territory in Florida. A charter for the southern section is given to a company of London merchants (called the London Company, until its successful colony causes it be known as the Virginia Company). A company based in Plymouth is granted a similar charter for the northern part of this long coastline, which as yet has no European settlers.

The Plymouth Company achieves little (and has no connection with the Pilgrim Fathers who establish a new Plymouth in America in 1620). The London Company succeeds in planting the first permanent English settlement overseas - but only after the most appalling difficulties.

In the Atlantic the reign of James I includes the founding of Bermuda as a British colony. Soon after his death settlement begins in Barbados - for a while one of England's fastest growing overseas possessions, receiving 18,000 settlers between 1627 and 1642. In America twelve English colonies are in existence by 1688, the end of the reign of James I's grandson, James II.

Colonial achievements eastwards are equally impressive. James I encourages the new East India Company in the early years of his reign, and in 1615 sends Thomas Roe as England's first ambassador to the Indian emperor. By the end of the century Bombay, Madras and Calcutta are fortified English trading stations.

In the Atlantic the reign of James I includes the founding of Bermuda as a British colony. Soon after his death settlement begins in Barbados - for a while one of England's fastest growing overseas possessions, receiving 18,000 settlers between 1627 and 1642. In America twelve English colonies are in existence by 1688, the end of the reign of James I's grandson, James II.

This second tussle is between those who want a local but reformed continuation of the Roman tradition (the Anglicans) and others wishing to purify the church of all innovations associated with hierarchical state religion (the Puritans).

Elizabeth, for the peace of the nation, has been content to hold the ring between these factions. The Stuarts are more concerned with having their own way.

Because of the tactful manner in which he has handled similar tensions in Scotland, all parties have high hopes of James I when he ascends the English throne in 1603. A small group of extremist Catholics are rapidly disappointed in him. They fatally damage their own cause when they attempt murder and treason in the Gunpowder Plot of 1605 - an event which confirms, for centuries to come, an anti-Catholic obsession in the English national psyche.

The Puritans receive apparent encouragement when James calls a conference at Hampton Court in 1604 to consider the fairly modest programme of reform put forward in their Millenary petition (so called because it is supposedly supported by a thousand clergy).

In the event they too are disappointed. The king dismisses their proposals outright, insisting that the church will be organised his way - which means with bishops. Bishops are essential in a state religion, heading a hierarchy through which the monarch may hope to control the church, but they have no place in a presbyterial system.

The controversy over bishops becomes a central issue in the first two Stuart reigns, and particularly in that of Charles I - partly because he is a less indolent character than his father, and partly because he has, in William Laud, a vigorously authoritarian archbishop fighting on his behalf.

The matter comes to a head in the aptly named Bishops' Wars of 1639-40. These wars, in turn, lead directly into the English Civil War.

The Scottish wars would not necessarily have this result but for another antagonism which the first two Stuart kings seem obsessively determined to foster - in the ever-escalating struggle between themselves and the parliament in Westminster.

The Puritan movement

By the 1660s Puritanism was firmly established

amongst the gentry and the emerging middle classes of southern and eastern

England, and during the Civil Wars the Puritan "Roundheads" fought

for the parliamentary cause and formed the backbone of Cromwell's forces during

the Commonwealth period. After 1646, however, the Puritan emphasis upon

individualism and the individual conscience made it impossible for the movement

to form a national Presbyterian church, and by 1662, when the Anglican church

was re-established, Puritanism had become a loose confederation of various

Dissenting sects. The growing pressure for religious toleration within Britain

itself was to a considerable degree a legacy of Puritanism, and its emphasis on

self-discipline, individualism, responsibility, work, and asceticism was also

an important influence upon the values and attitudes of the emerging middle classes.

The Gunpowder Plot

The Gunpowder

Plot of 1605, in earlier

centuries often called the Gunpowder

Treason Plot or the Jesuit Treason, was a failed

assassination attempt against King James I of

England and IV of Scotland by a group of provincial English Catholics led by

Robert Catesby The plan was to blow up the House of Lords during the State Opening Of England´s Parliament on

5 November 1605, as the prelude to a popular revolt in the Midlands during which James's

nine-year-old daughter, Princess Elizabeth

was to be installed as the Catholic head of

state. Catesby may have embarked on the scheme after hopes of securing

greater religious tolerance under King James had faded, leaving many English

Catholics disappointed. His fellow plotters were John Wright, Thomas Wintour, Thomas Percy, Guy Fawkes, Robert Keyes, Thomas Bates, Robert Wintour, Christopher

Wright, John Grant, Ambrose

Rookwood, Sir Everard

Digby and Francis Tresham. Fawkes, who had 10 years of military experience fighting in the Spanish

Netherlands in suppression of the Dutch Revolt, was given charge of the explosives.

The plot was revealed to the authorities in

an anonymous letter sent to William Parker, 4th Baron Monteagle, on 26 October 1605. During a search of

the House of Lords at about midnight on 4 November 1605, Fawkes was

discovered guarding 36 barrels of gunpowder—enough

to reduce the House of Lords to rubble—and arrested. Most of the conspirators

fled from London as they learnt of the plot's discovery,

trying to enlist support along the way. Several made a stand against the

pursuing Sheriff of Worcester and his men at Holbeche House; in the ensuing battle Catesby was one of those shot and killed. At

their trial on 27 January 1606, eight of the survivors, including Fawkes,

were convicted and sentenced to be hanged, drawn and quartered.

The plot was revealed to the authorities in

an anonymous letter sent to William Parker, 4th Baron Monteagle, on 26 October 1605. During a search of

the House of Lords at about midnight on 4 November 1605, Fawkes was

discovered guarding 36 barrels of gunpowder—enough

to reduce the House of Lords to rubble—and arrested. Most of the conspirators

fled from London as they learnt of the plot's discovery,

trying to enlist support along the way. Several made a stand against the

pursuing Sheriff of Worcester and his men at Holbeche House; in the ensuing battle Catesby was one of those shot and killed. At

their trial on 27 January 1606, eight of the survivors, including Fawkes,

were convicted and sentenced to be hanged, drawn and quartered.Stuart rule in England: AD 1603-1642

Stuart rule in England can be characterized by three main themes, each of them

evident early in the reign of James I. One is the relationship with parliament; here James begins so badly

that within a year the commons feel compelled to issue a document, known as the Apology, asserting their rights. Another is the continuing

hostility between Christian sects. Again the early omens are unpromising. James

profoundly offends the Puritans at Hampton

Court in 1604, and is

nearly blown up by the Catholics in the Gunpowder

Plot of 1605.

The third theme is the beginning of the British empire. In this area the

new Stuart regime can claim greater success.

Virginia: AD 1607-1644In 1606 James I supports new English efforts (the first since Raleigh) to establish colonies along the coast of America, north of the Spanish-held territory in Florida. A charter for the southern section is given to a company of London merchants (called the London Company, until its successful colony causes it be known as the Virginia Company). A company based in Plymouth is granted a similar charter for the northern part of this long coastline, which as yet has no European settlers.

The Plymouth Company achieves little (and has no connection with the Pilgrim Fathers who establish a new Plymouth in America in 1620). The London Company succeeds in planting the first permanent English settlement overseas - but only after the most appalling difficulties.

In the Atlantic the reign of James I includes the founding of Bermuda as a British colony. Soon after his death settlement begins in Barbados - for a while one of England's fastest growing overseas possessions, receiving 18,000 settlers between 1627 and 1642. In America twelve English colonies are in existence by 1688, the end of the reign of James I's grandson, James II.

Colonial achievements eastwards are equally impressive. James I encourages the new East India Company in the early years of his reign, and in 1615 sends Thomas Roe as England's first ambassador to the Indian emperor. By the end of the century Bombay, Madras and Calcutta are fortified English trading stations.

In the Atlantic the reign of James I includes the founding of Bermuda as a British colony. Soon after his death settlement begins in Barbados - for a while one of England's fastest growing overseas possessions, receiving 18,000 settlers between 1627 and 1642. In America twelve English colonies are in existence by 1688, the end of the reign of James I's grandson, James II.

Stuarts and the religion: AD (1603-1640)

Since the reigns of Edward VI and Mary I two separate

religious struggles run, like interwoven threads, through English life. One is

the attempt, clandestine except in Mary's reign, to restore the country to

Rome. The other is a battle for the soul of an English church. This second tussle is between those who want a local but reformed continuation of the Roman tradition (the Anglicans) and others wishing to purify the church of all innovations associated with hierarchical state religion (the Puritans).

Elizabeth, for the peace of the nation, has been content to hold the ring between these factions. The Stuarts are more concerned with having their own way.

Because of the tactful manner in which he has handled similar tensions in Scotland, all parties have high hopes of James I when he ascends the English throne in 1603. A small group of extremist Catholics are rapidly disappointed in him. They fatally damage their own cause when they attempt murder and treason in the Gunpowder Plot of 1605 - an event which confirms, for centuries to come, an anti-Catholic obsession in the English national psyche.

The Puritans receive apparent encouragement when James calls a conference at Hampton Court in 1604 to consider the fairly modest programme of reform put forward in their Millenary petition (so called because it is supposedly supported by a thousand clergy).

In the event they too are disappointed. The king dismisses their proposals outright, insisting that the church will be organised his way - which means with bishops. Bishops are essential in a state religion, heading a hierarchy through which the monarch may hope to control the church, but they have no place in a presbyterial system.

The controversy over bishops becomes a central issue in the first two Stuart reigns, and particularly in that of Charles I - partly because he is a less indolent character than his father, and partly because he has, in William Laud, a vigorously authoritarian archbishop fighting on his behalf.

The matter comes to a head in the aptly named Bishops' Wars of 1639-40. These wars, in turn, lead directly into the English Civil War.

The Scottish wars would not necessarily have this result but for another antagonism which the first two Stuart kings seem obsessively determined to foster - in the ever-escalating struggle between themselves and the parliament in Westminster.

The Puritan movement

The Puritan movement was a broad trend toward a

militant, biblically based Calvinistic Protestantism -- with emphasis upon the

"purification" of church and society of the remnants of

"corrupt" and "unscriptural" "papist" ritual and

dogma -- which developed within the late sixteenth- and early

seventeenth-century Church

of England. Puritanism first emerged as an organized force in England among

elements -- Presbyterians, Independents, and Baptists, for example --

dissatisfied with the compromises inherent in the religious settlement carried

out under Queen Elizabeth in 1559.

They sought a complete reformation both of

religious and of secular life, and advocated, in consequence, the attacks upon

the Anglican establishment, the emphasis upon a disciplined, godly life, and

the energetic evangelical activities which characterized their movement. The Presbyterian wing of the Puritan party was

eventually defeated in Parliament, and after the suppression in 1583 of

Nonconformist ministers, a minority moved to separate from the church and

sought refuge first in the Netherlands and later in New England .

|

Gallery of famous

17th-century Puritan theologians:

. Thomas Manton, John Flavel, Richard Sibbes, Stephen Charnock, William Bates, John Owen, John Howe,

Richard Baxter.

|

James I and taxation: AD 1603-1625

The balance of advantage between king and parliament derives from two established facts. One favours the king. Only he can summon a parliament, so parliament is powerless without him.

But only parliament can raise the necessary taxes to run the kingdom. This is a traditional right, but it is also a practical reality; the members' local influence in their districts will be an important factor in securing the funds. So in this other sense the king is powerless without parliament.

The Stuart kings attempt to break the impasse by not calling parliament and by finding other ways to raise funds. These include the sale of baronetcies and peerages, the demanding of gifts (payments discreetly known as "benevolences"), and the letting out of trade monopolies. Such measures are not well calculated to please the likely members of the next parliament, fuming in the provinces as they await the unpredictable call to Westminster.

In 1614 James is so short of funds that he calls a parliament, the first in four years. But the members are in no mood to discuss anything other than their own grievances. Not a single bill is passed in two months. The outraged king dissolves what becomes known as the Addled Parliament.

Seven years elapse before James calls another parliament, in 1621. This time the commons find a new way of fighting back. They revive a medieval right by which the commons can impeach a public servant, sending him for trial before the House of Lords. Two purchasers of royal monopolies are the first to be brought to heel by this device. They are followed by a bigger catch - Francis Bacon, the Lord Chancellor, who admits to accepting money from litigants.

The message is clear. Parliament is to be the highest authority in the land. With the beginning of a new reign, in 1625, the point is driven forcefully home in the sensitive area of taxation.

The balance of advantage between king and parliament derives from two established facts. One favours the king. Only he can summon a parliament, so parliament is powerless without him.

But only parliament can raise the necessary taxes to run the kingdom. This is a traditional right, but it is also a practical reality; the members' local influence in their districts will be an important factor in securing the funds. So in this other sense the king is powerless without parliament.

The Stuart kings attempt to break the impasse by not calling parliament and by finding other ways to raise funds. These include the sale of baronetcies and peerages, the demanding of gifts (payments discreetly known as "benevolences"), and the letting out of trade monopolies. Such measures are not well calculated to please the likely members of the next parliament, fuming in the provinces as they await the unpredictable call to Westminster.

In 1614 James is so short of funds that he calls a parliament, the first in four years. But the members are in no mood to discuss anything other than their own grievances. Not a single bill is passed in two months. The outraged king dissolves what becomes known as the Addled Parliament.

Seven years elapse before James calls another parliament, in 1621. This time the commons find a new way of fighting back. They revive a medieval right by which the commons can impeach a public servant, sending him for trial before the House of Lords. Two purchasers of royal monopolies are the first to be brought to heel by this device. They are followed by a bigger catch - Francis Bacon, the Lord Chancellor, who admits to accepting money from litigants.

The message is clear. Parliament is to be the highest authority in the land. With the beginning of a new reign, in 1625, the point is driven forcefully home in the sensitive area of taxation.

SOCIETY

Charles I

At the time of his birth in 1600, Charles was the second son of James VI of

Scotland. However, even by that time, it was clear that his father was going to

succeed Elizabeth I on the English throne, which he did after her death in

1603. Charles was moved to England in the following year, and in 1605 made duke

of York, but it was only in 1612, with the death of his older brother Henry,

that he became heir to the throne. In December 1624, he married Princess

Henrietta Maria of France, whose court was often to become a source of some

embarrassment to Charles, and he and his father promised toleration for the

English Catholics, another source of tension. Only three months later, on 27

March 1625, Charles came to the throne.

During

the 17th century the population of England and Wales grew steadily. It was

about 4 million in 1600 and it grew to about 5 1/2 million by 1700.

During

the 17th century England became steadily richer. Trade and commerce grew and

grew. By the late 17th century trade was an increasingly important part of the

English economy. Meanwhile industries such as glass, brick making, iron and

coal mining expanded rapidly.

During

the 17th century the status of merchants improved. People saw that trade was an

increasingly important part of the country's wealth so merchants became more

respected. However political power and influence was held by rich landowners.

At

the top of English society were the nobility. Below them were the gentry.

Gentlemen were not quite rich but they were certainly well off. Below them were

yeomen, farmers who owned their own land. Yeomen were comfortably off but they

often worked alongside their men. Gentlemen did not do manual work! Below them

came the mass of the population, craftsmen, tenant farmers and labourers.

At

the end of the 17th century a writer estimated that half the population could

afford to eat meat every day. In other words about 50% of the people were

wealthy of at least reasonably well off. Below them about 30% of the population

could afford to eat meat between 2 and 6 times a week. They were 'poor'. The

bottom 20% could only eat meat once a week. They were very poor. At least part of the time they had to rely on poor relief.

By an

act of 1601 overseers of the poor were appointed by each parish. They had power

to force people to pay a local tax to help the poor. Those who could not work

such as the old and the disabled would be provided for. The overseers were

meant to provide work for the able-bodied poor. Anyone who refused to work was

whipped and, after 1610, they could be placed in a house of correction.

Pauper's children were sent to local employers to be apprentices.

On a

more cheerful note in the 17th century in many towns wealthy people left money

in their wills to provide almshouses where the poor could live.

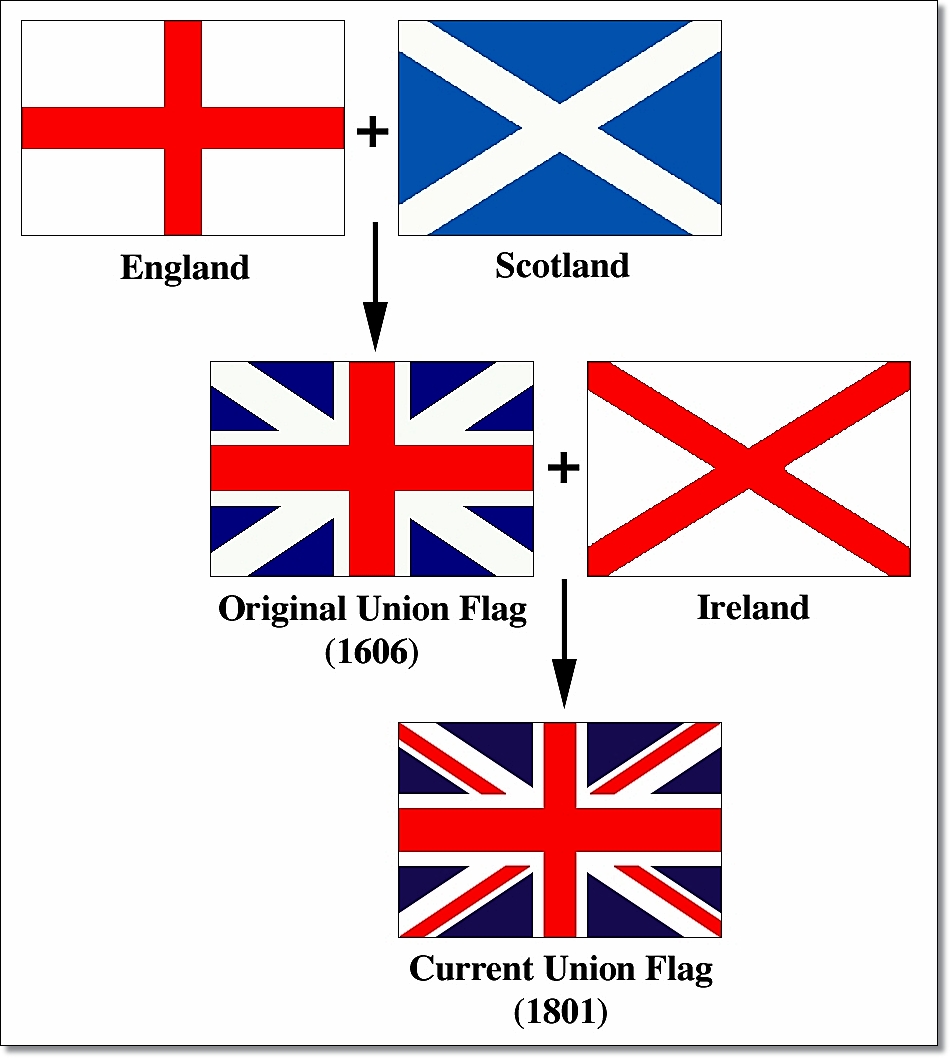

THE UNION FLAG

THE UNION FLAG

In 1606, the

first flag of Great Britain was developed, which included the crosses of

England and Scotland (at this point, Ireland had not been united with England

or Scotland).

The red vertical cross

(England) had to be put onto the white on blue cross (Scotland) and a white

border was added for reasons of Heraldry.

This flag was

used during the reign of James 1st & Charles 1st (1603 to 1649) and

up until 1801. In that year Ireland became united officially with England. King

George III then updated the design by adding the Cross of St Patrick.

The designers of the day had to ensure that all the crosses could be

recognized as individual flags as well as existing in the same flag together.

They achieved this by making the white background (Scottish Cross) broader on

one side of the Irish red than on the other, this meant that all of the

individual crosses could be clearly recognized & the Irish Cross had its

original white background.

In 1600 Westminster was separate from London. However

in the early 17th century rich people built houses along the Thames between the

two. In the late 17th century many grand houses were built west of London.

Meanwhile working class houses were built east of the city. So as early as the

17th century London was divided into the affluent west end and the poor east

end.

Stuart towns were dirty and unsanitary. People threw

dirty water and other rubbish in the streets. Furthermore the streets were very

narrow. At night they were dark and dangerous.

However there were some improvements in London. In the

early 17th century a piped water supply was created. Water from a reservoir

travelled along elm pipes through the streets then along lead pipes to

individual houses. However you had to pay to be connected to the supply and it

was not cheap.

In 1600 people in London walked from one street to

another or if they could afford it they travelled by boat along the Thames.

However from the early 17th century you could hire a horse drawn carriage

called a hackney carriage to take you around London.

In the 1680s the streets of London were lit for the

first time. An oil lamp was hung outside every tenth house and was lit for part

of the year. The oil lamps did not give much light but they were better than

nothing at all.

During the 17th century towns grew much larger. That

was despite outbreaks of plague. Fleas that lived on rats transmitted bubonic

plague. If the fleas bit humans they were likely to fall victim to the disease.

Unfortunately at the time nobody knew what caused the plague and nobody had any

idea how to treat it.

Plague broke out in London in 1603, 1636 and in 1665.

Each time it killed a significant part of the population but each time London

recovered. There were always plenty of poor people in the countryside willing

to come and work in the town. Of course, other towns as well as London were

also periodically devastated by the plague. However the plague of 1665, which

affected London and other towns, was the last. We are not certain

why.

The

population of London was about 250,000 by 1600 and during the 17th century the

suburbs outside London continued to grow. In the late 16th century rich men

began to build houses along the Strand and by 1600 London was linked to

Westminster by a strip of houses.

Banqueting

House was built in 1622. In 1635 the king opened Hyde Park to the public. In

1637 Charles I created Richmond Park for hunting. Also in 1637 Queens House was

completed in nearby Greenwich.

Wool

was still the main export from London but there were also exports of 'Excellent

saffron in small quantities, a great quantity of lead and tin, sheep and rabbit

skins without number, with various other sorts of fine peltry (skins) and

leather, beer, cheese and other sorts of provisions'. The Royal Exchange where

merchants could buy and sell goods opened in 1571.

In

the early 17th century rich men continued to build houses west of London. The

Earl of Bedford built houses at Covent Garden, on the Strand and at Long Acre.

He also obtained permission to hold a fruit and vegetable market at Covent

Garden. Other rich people build houses at Lincoln Inn Fields and at St Martins

in the Fields.

On

the other side of London hovels were built. The village of Whitechapel was

'swallowed up' by the expanding city. The village of Clerkenwell also became a

suburb of London. Southwork also

grew rapidly.

All

this happened despite outbreaks of bubonic plague. It broke out in 1603, 1633

and 1665 but each time the population of London quickly recovered.

In

1642 civil war began between king and parliament. The royalists made one

attempt to capture London in 1643 but their army was met 6 miles west of St

Pauls by a much larger parliamentary army. The royalists withdrew. However the

Puritan government of 1646-1660 was hated by many ordinary people and when

Charles II came to London from France in 1660 an estimated 20,000 people

gathered in the streets to meet him. All the churches in London

rang their bells.

The

last outbreak of plague in London was in 1665. But this was the last outbreak.

Bubonic Plague, known as the Black Death, first hit the British Isles in

1348, killing nearly a third of the population. Although regular outbreaks of

the plague had occurred since, the outbreak of 1665 was the worst case since

1348.

London had

changed little since this engraving was made in 1480. Houses were tightly

packed together and conditions insanitary - ideal conditions for the plague to

spread, particularly during the hot summer of 1665.

When plague

broke out in Holland in 1663, Charles II stopped trading with the country in an

attempt to prevent plague infested rats arriving in London. However, despite

these precautions, plague broke out in the capital in the Spring of 1665.

Spread by the blood-sucking fleas that lived on the black rat.

The Summer of

1665 was one of the hottest summers recorded and the numbers dying from plague

rose rapidly. People began to panic and the rich fled the capital. By June it

was necessary to have a certificate of health in order to travel or enter

another town or city and forgers made a fortune issuing counterfeit

certificates.

The temperature

and the numbers of deaths continued to rise. The Lord Mayor of London,

desperate to be seen to be doing something, heard rumours that it was the stray

dogs and cats on the streets that were spreading the disease and ordered them

to be destroyed. This action unwittingly caused the numbers of deaths to rise

still further since there were no stray dogs and cats to kill the rats.

Those houses that

contained plague victims were marked with a red cross. People only ventured

into the streets when absolutely necessary preferring the 'safety' of their own

homes. Carts were driven through the streets at night. The driver's call of

'bring out yer dead' was a cue for those with a death in the house to bring the

body out and place it onto the cart. Bodies were then buried in mass graves.

The numbers of

deaths from the plague reached a peak in August and September of 1665. However,

it was November and the onset of cold weather that brought a drastic reduction

in the number of deaths. Charles II did not consider it safe to return to the

capital until February 1666.

In 1666 came the great fire of London. It

began on 2 September in a baker's house in Pudding Lane. At first it did not

cause undue alarm. The Lord Mayor was awoken and said "Pish! A woman might

piss it out!". But the wind caused the flames to spread rapidly. People

formed chains with leather buckets and worked hand operated pumps all to no

avail. The mayor was advised to use gunpowder to create fire breaks but he was

reluctant, fearing the owners of destroyed buildings would sue for

compensation. The fire continued to spread until the king took charge. He

ordered sailors to make fire breaks. At the same time the wind dropped.

About

13,200 houses had been destroyed and 70-80,000 people had been made homeless.

The king ordered the navy to make tents and canvas available from their stores

to help the homeless who camped on open spaces around the city. Temporary

markets were set up so the homeless could buy food. but the crowds of homeless

soon dispersed. Most of the houses in London were still standing and many of

the homeless found accommodation in them or in nearby villages. Others built

wooden huts on the charred ruins.

To

prevent such a disaster happening again the king commanded that all new houses

in London should be of stone and brick not wood. Citizens were responsible for

rebuilding their own houses but a tax was charged on coal brought by ship into

London to finance the rebuilding of churches and other public buildings. Work began

on rebuilding St Pauls in 1675 but it was not finished till 1711.

In the late 17th century fashionable houses were built at Bloomsbury and on the road to the village of Knightsbridge. Elegant houses in squares and broad straight streets were also built north of St James palace. Soho also became built up. As well as building attractive suburbs the rich began to live in

In the late 17th century fashionable houses were built at Bloomsbury and on the road to the village of Knightsbridge. Elegant houses in squares and broad straight streets were also built north of St James palace. Soho also became built up. As well as building attractive suburbs the rich began to live in

attractive villages near London such as Hackney, Clapham Camberwell and Streatham. In the east the poor continued to build houses and Bethnal Green was 'swallowed up' by the growing city.

Charles I

Right from the start, he clashed with Parliament. Prompted by family tied,

Charles had promised aid to Frederick V, Elector Palatine, heavily engaged in

the first years of the Thirty Years War, who was married to Charles's sister Elizabeth,

and had agreed to fund an English force which would join Frederick's general

Ernst von Mansfeld. However, Charles's first Parliament, already hostile to his

favourite, the duke of Buckingham, refused to fully fund this overseas venture.

Involvement in the Thirty Years War continued, with a disastrous attempt

against Cadiz in 1626, and another, equally disastrous attempt to help the

Protestants of Rochelle in 1627, after which Charles made peace with both

France (1629) and Spain (1630). The clashes with Parliament had continued,

especially over religion, where Parliament was Calvinist, while Charles was

suspiciously High Church, and was always suspected of pro-Catholic leaning. His

third Parliament saw the signing of the 'petition of right' (June 1628),

largely led by Sir Thomas Wentworth (soon to become earl of Strafford).

Parliament was dissolved on 10 March 1629, beginning the Eleven Years Tyranny,

during which Charles ruled without Parliament.

Charles now set about destroying his support. To fund his government, he

revived a series of out of date sources of income, starting with tonnage and

poundage in 1629, followed by fines for not taking up knighthood, and huge

fines for encroaching of forest lands in 1630, and most famously, the demanding

of Ship Money from 1634. At the same time, he was causing religious offence by his

support for Archbishop Laud, a follower of the anti-Calvinist theologian

Jacobus Arminius, who from 1633 was attempting to force the Puritanical party

in the Church to accept church ceremonial.

It was his church policy that led to trouble with Scotland. At his Scottish

coronation in 1633, he had caused offence with the level of ceremonial he

required. In 1637, he attempted to impose a new liturgy on Scotland, drawn up

by Laud, and further from Scottish practise than even the English liturgy of

the period. In response, the Scots signed a National Covenant, reaffirming

their opposition to the Catholic church, and to Charles's religious policies,

and in November 1638 a general assembly abolished the bishops. Charles was

furious, and raised an army, intending to invade Scotland (First Bishop's War, 1639), but he ran out of money, and after signing

the Treaty of Berwick, decided to summon Parliament to raise funds for a renewed war. However,

this Short Parliament (April-May 1640), led by John Pym, made it clear that they

agreed with the Scots, and demanded to discuss the Scottish complaints first,

at which point Charles dissolved it. The Scots now invaded England (Second Bishop's War), and captured Newcastle and Durham, forcing

Charles to summon Parliament again.

The Long Parliament (November 1640-1660), was just as hostile as the Short had been.

Within six months, it had achieved the execution of Wentworth, now earl of

Strafford, and a key supporter of Charles, and had forced Charles to agreed not

to dissolve Parliament without it's own agreement. However, for much of the

rest of 1641, Parliament was deadlocked over Religion, and only a series of

blunders by Charles led to war. In October 1641, rebellion had broken out in

Ireland, and many in Parliament suspected Charles of at least prior knowledge.

However, when he returned to London in November 1641, Charles was so well

received that he decided to resist Parliament, culminating on 4 January 1642

with his attempt to arrest the 'five members' of the House of Commons, with

united Parliament against him. On 10 January Charles left to collect troops,

while Parliament moved to gain control of the militia. Finally, on 22 August

1642, Charles raised his standard at Nottingham, beginning the First Civil War.

From Nottingham, Charles moved west across the midlands, and into the Welsh

marches, gathering an army, before on 12 October leaving Shrewsbury to march on

London. Parliament sent Essex to stop him, and the two sides met in the battle of Edgehill (23

October), the first major battle of

the war, and a draw. However, the result led to gloom in London, and Charles

had a brief chance to capture his capitol. By the time he was ready to make

that move, the mood of London had recovered, and Charles was faced by the

trained bands of London at Turnham Green (13 November), after which he

retreated to Oxford to spend the winter, concentrating on expanding the area he

held around the city.

His next move was to besiege Gloucester, held for Parliament by Colonel Massey. Charles

and his army arrived before the city on 10 August 1643, but the city held, and

he was forced to abandon the siege on 8 September by the arrival of Essex.

However, this gave Charles another chance for victory - if he could cut off

Essex's retreat to London, and defeat him on a well chosen battlefield, London

would have been exposed. However, Charles did not manage his march well, and

when battle came (1st battle of Newbury, 20 September 1643), the result was inconclusive. However, after

the battle Charles decided to march away to Oxford, leaving Essex free to

return to London with his army intact.

Charles spend much of the next few months in Oxford, only leaving at the

start of June 1644 when the city came under threat. After a short period of

movement, Charles won a victory at Cropredy Bridge (29 June 1644), which much

weakened Waller's army. Much of the gloss was taken off this victory by the defeat of Prince Rupert at Marston Moor (2 July), but one of Charles's failings during the civil

war was an inability to understand the magnitude of some of his defeats. His

response was to confirm an earlier intention to move against Essex, currently

in the west country, where he had attempted to capture the Queen. The two

armies came together around Lostwithel, and fought two battles, starting with

Beacon Hill (21 August 1644), an ambitious attack on a four mile front by

Charles, which achieved it's limited objectives and pined Essex and his army

down. The second battle, Castle Dore (31 August-1 September 1644), which saw

the surrender of 6,000 men, the remains of Essex's army, although Essex himself

escaped. This Lostwithel campaign saw Charles I at his best as a commander,

controlling a complex series of attacks that led to the defeat of one of

Parliament's best armys. In many ways, it was Charles's high point during the

war. Charles now moved slowly out of the west country, with the limited

intention of relieving the sieges of Banbury Castle, Basing House and

Donnington Castle. Parliament managed to bring together a large army, but at

the 2nd battle of Newbury (27 October 1644), the divided command of the

Parliamentary army allowed the King's much smaller army to escape, reaching Oxford

on 1 November. His army was now 15,000 strong, and for the first time under the

command of Prince Rupert. Moreover,

Parliament now abandoned the three sieges in question.

The plan agreed on for 1645 was for Charles's army to march north to relief

Chester, then attack the Scottish army, then besieging Pontefract. Charles

marched on 9 May, and soon heard that the siege of Chester had been lifted. At

the end of May, Prince Rupert captured Leicester, and Charles was in good

spirits. That was soon to change. On 14 June, Charles's army came up against

the New Model Army under Fairfax at the battle of Naseby, and was soundly defeated. Charles himself

escaped the field, and managed to work his way to Hereford, where he began to

raise another army. For the next few months he kept on the move, from Cardiff

on 5 August, to Doncaster on 18 August, Huntingdon on 24 August, then back to

Oxford, before returning to Hereford on 4 September. Meanwhile, news of Naseby

had disheartened many besieged Royalist strongholds, and Charles's position was

becoming increasingly dangerous. Even Prince Rupert found himself under

suspicion, and after surrendering Bristol in September, Charles dismissed him

from command, and ordered him to leave the country. Charles meanwhile moved

once again to relieve Chester, besieged again, but on 24 September was forced

to watch as his cavalry was defeated (Rowton Heath). Although Chester held on

for another five months (until 3 February 1646), Charles decided to move on,

and by mid-October was based at Newark. Even Charles could now see that the war

was lost, and made renewed efforts to split his enemies diplomatically, sensing

that there were growing divides between the Presbyterian Scots and the largely

Independent New Model Army. It was this that prompted Charles into one last

desperate gamble, and on 27 April 1646 he left his own camp at Oxford to surrender

to the Scots, now besieging Newark.

Charles's hopes of turning the Scots into his allies did not last. Their

demands for Presbyterianism to be imposed on England were unacceptable to him,

and after they received a third of their back pay, the Scots handed Charles

over to Parliament in January 1647. After nearly a year in confinement, on 11

November 1647, Charles managed to escape from imprisonment in Hampton Court,

and make his way to Carisbrooke Castle on the Isle of Wight, where although he

was held captive, he was free to negotiate with all sides. On 26 December he

signed the 'Engagement' with the Scots, in which he agreed to impose

Presbyterianism on England, in return for Scottish aid in regaining power. The

ensuing Second Civil War saw all of Charles's remaining support defeated, and, worse for him,

removed any last feeling of loyalty in Parliament, now convinced that they

could never again trust Charles. Charles now dug his heals in, and refused to

make any concession. Meanwhile, Pride's Purge left the army in command, and

determined to be rid of Charles. After a brief, and deeply suspect trial,

Charles I was executed in Whitehall on 30 January 1649, not the first English

monarch to be deposed and killed, but the first to suffer that fate in public.

In 1653, Cromwell

was installed as 'lord protector' of the new Commonwealth of England, Scotland

and Ireland. Over the next five years, he strove to establish broad-based

support for godly republican government with scant success.

Fall of the republic

In the wake of the king´s execution a republican regimewas established in England, a regime which was chiefly underpinned by the stark military power of the New Model Army.

England's new rulers were determined to re-establish England's traditional

dominance over Ireland, and in 1649 they sent a force under Oliver Cromwell to

undertake the reconquest of Ireland, a task that was effectively completed by

1652.

Meanwhile, Charles I's eldest son had come to an agreement with the Scots

and in January 1651 had been crowned as Charles II of Scotland. Later that

year, Charles invaded England with a Scottish army, but was defeated by

Cromwell at Worcester.

The young king just

managed to avoid capture, and later escaped to France. His Scottish subjects

were left in a sorry plight, and soon the Parliamentarians had conquered the

whole of Scotland.

Cromwell died in

1658 and was succeeded as protector by his son, Richard, but Richard had little

aptitude for the part he was now called upon to play and abdicated eight months

later.

After Richard

Cromwell's resignation, the republic slowly fell apart and Charles II was

eventually invited to resume his father's throne. In May 1660, Charles II

entered London in triumph. The monarchy had been restored.

Charles II was an

intelligent but deeply cynical man, more interested in his own pleasures than

in points of political or religious principle. His lifelong preoccupation with

his many mistresses did nothing to improve his public image.

The early years

of the new king's reign were scarcely glorious ones. In 1665 London was

devastated by the plague, while a year later much of the capital was destroyed

in the Great Fire of London.

The Dutch raid on

Chatham in 1667 was one the most humiliating military reverses England had ever

suffered.

Nevertheless, the

king was a cunning political operator and when he died in 1685 the position of

the Stuart monarchy seemed secure. But things swiftly changed following the

accession of his brother, James, who was openly Catholic.

James II at once

made it plain that he was determined to improve the lot of his Catholic

subjects, and many began to suspect that his ultimate aim was to restore

England to the Catholic fold.

The birth of

James's son in 1688 made matters even worse since it forced anxious Protestants

to confront the fact that their Catholic king now had a male heir.

Soon afterwards,

a group of English Protestants begged the Dutch Stadholder William of Orange -

who had married James II's eldest daughter, Mary, in 1677 - to come to their

aid.

Oliver Cromwell: (English soldier and statesman who helped make England a republic and then ruled as lord protector from 1653 to 1658)

Oliver Cromwell

was born into a family which was for a time one of the wealthiest and most

influential in the area.

Educated at

Huntingdon grammar school , now the Cromwell Museum, and at Cambridge

University, he became a minor East Anglian landowner. He made a living by

farming and collecting rents, first in his native Huntingdon, then from 1631 in

St Ives and from 1636 in Ely. Cromwell's inheritances from his father, who died

in 1617, and later from a maternal uncle were not great, his income was modest

and he had to support an expanding family – widowed mother, wife and eight

children. He ranked near the bottom of the landed elite, the landowning class

often labelled 'the gentry' which dominated the social and political life of

the county. Until 1640 he played only a small role in local administration and

no significant role in national politics. It was the civil wars of the 1640s

which lifted Cromwell from obscurity to power.

Cromwell's

military standing gave him enhanced political power, just as his military

victories gave him the confidence and motivation to intervene in and to shape

political events. An obscure and inexperienced MP for Cambridge in 1640, by the

late 1640s he was one of the power-brokers in parliament and he played a

decisive role in the 'revolution' of winter 1648-9 which saw the trial and

execution of the King and the abolition of monarchy and the House of Lords. As

head of the army, he intervened several times to support or remove the

republican regimes of the early 1650s.

In December

1653, he became head of state as Lord Protector, though he held that office

under a written constitution which ensured that he would share political power

with parliaments and a council. As Lord Protector for almost five years, until

his death on 3 September 1658, Cromwell was able to mould policies and to

fulfill some of his goals. He headed a tolerant, inclusive and largely civilian

regime, which sought to restore order and stability at home and thus to win

over much of the traditional political and social elite. Abroad, the army and

navy were employed to promote England's interests in an expansive and largely

successful foreign policy.

From the

outbreak of war in summer 1642, Cromwell was an active and committed officer in

the parliamentary army. Initially a captain in charge of a small body of

mounted troops, in 1643 he was promoted to colonel and given command of his own

cavalry regiment.

He was

successful in a series of sieges and small battles which helped to secure East

Anglia and the East Midlands against the royalists. At the end of the year he

was appointed second in command of the Eastern Association army, parliament's

largest and most effective regional army, with the rank of lieutenant-general.

During 1644 he contributed to the victory at Marston Moor, which helped secure

the north for parliament, and also campaigned with mixed results in the south

Midlands and Home Counties.

In 1645-6, as

second in command of the newly formed main parliamentary army, the New Model

Army, Cromwell played a major role in parliament's victory in the Midlands,

sealed by the battle of Naseby in June 1645, and in the south and south-west.

When civil war flared up again in 1648 he commanded a large part of the New

Model Army which first crushed rebellion in South Wales and then at Preston

defeated a Scottish-royalist army of invasion.

After the trial

and execution of the King, Cromwell led major military campaigns to establish

English control over Ireland (1649-50) and then Scotland (1650-51), culminating

in the defeat of another Scottish-royalist army of invasion at Worcester in

September 1651. In summer 1650, before embarking for Scotland, Cromwell had

been appointed lord general - that is, commander in chief - of all the

parliamentary forces.

It was a

remarkable achievement for a man who probably had no military experience before

1642. Cromwell consistently attributed his military success to God's will.

Historians point to his personal courage and skill, to his care in training and

equipping his men and to the tight discipline he imposed both on and off the

battlefield.

Cromwell life

and actions had a radical edge springing from his strong religious faith. A

conversion experience some time before the civil war, strengthened by his

belief that during the war he and his troops had been chosen by God to perform

His will, gave a religious tinge to many of his political policies as Lord

Protector in the 1650s. Cromwell sought 'Godly reformation', a broad programme

involving reform of the most inhumane elements of the legal, judicial and

social systems and clamped down on drunkenness, immorality and other sinful

activities. He also believed passionately in what he called 'liberty of

conscience', that is freedom for a range of Protestant groups and faiths to

practise their beliefs undisturbed and without disturbing others. Several times

he referred to this religious liberty as the principal achievement of the wars,

to be strengthened and cherished now that peace had returned. Others, however,

viewed these religious policies as futile, unnecessarily divisive or a breeding

ground for heresy.

Cromwell's son Richard was named as his

successor and was lord protector of England from September 1658 to May 1659. He

could not reconcile various political, military and religious factions and soon

lost the support of the army on which his power depended. He was forced to

abdicate and after the restoration of the monarchy in 1660 he fled to Paris. He

returned to England in 1680 and lived quietly under an assumed name until his

death in 1712.

No comments:

Post a Comment